SOURCE: MONSTER CHILDREN AUTHOR: MONIQUE PENNING

DATE: JULY 6, 2020 FORMAT: DIGITAL

BRIGHT YOUNG THINGS

It says a whole lot about the year 2020 that when I catch Grace Ahlbom on the phone location scouting on Google Maps and watching guitar tutorials on YouTube. An invisible respiratory virus has the New York-based photographer stuck firmly indoors, but it’s obviously not doing much to stunt her creativity. The talented 20-something dabbles in all manner of image-making—zines, fashion editorials, landscapes, sculptural works—but it’s her portraits that caught my eye first. Grace has an innate aptitude for making any person who steps in front of her lens—whether it’s Icelandic teenage boys, best friends, or Iggy Pop—look completely at ease. Her ability to tap into her subject’s genuine self is something that many try but only some succeed at, and it’s seen her draw the deserved interest of Supreme and Helmut Lang, and publications like the New York Times, GQ and, well, us. I caught up with the East Village-bound photographer to find out more about big icons, small cameras, and everything in between.

Hey Grace! How you going?

I’m good, how are you?

I’m good, stuck inside a little bit. What are you doing have you been doing to pass the time?

That’s a good question. Right now, I’m location scouting for an editorial I’m working on, but like, via Google Maps. It’s going to be in Upstate New York, so I’m looking at caves and anything else interesting to shoot. But other than that, I got a guitar so I’ve been trying to teach myself some stuff.

Have you ever played before?

I did when I was younger, in sixth grade I took lessons, but I’ve been a lot more interested in actually learning this time around… Before it felt more like a chore. I’ve been watching YouTube tutorials about Neil Young songs; right now I’m learning ‘Heart of Gold’, but the my first song I learned was ‘Tonight, Tonight’ by The Smashing Pumpkins.

Is that one easy?

It said it was hard, but I guess when you don’t know what you’re doing in the first place, it’s hard to even tell what’s easy or hard. It’s all hard, so might as well just see

At least you’re a few steps ahead of ‘Smoke on the Water’.

Yeah, exactly, I couldn’t do that. That would just trigger me.

So, where are you now?

I live in the East Village now, and I moved back to New York in October from Los Angeles.

How long were you out there for?

About two years. But I lived in Brooklyn for six years; I went to Pratt Institute, and when I graduated I had the opportunity to go and do a residency at Soft Opening, which is a gallery in London. So, I ended up going to London and staying for about four months until I got kicked out—of the country, not where I was staying—and then instead of returning to New York, I decided to give Los Angeles a try. I was kind of over New York and I’d always been interested in LA, so I just went for it. But after a while, I started noticing all the things I loved about New York. I never realised how accustomed I was to the hustle and bustle.

What did you miss about it?

Los Angeles was just too isolating for me. I never ran into anyone, which is the exact opposite of New York. And I crave the energy that New York gives off, I feel like I just need to be reminded of people more often, and I think that has an effect on me creatively as well.

And you’re from San Francisco originally?

Yeah, but more from Marin County which is just across the Golden Gate Bridge. It was great, I spent a lot of my teenage years exploring the most beautiful parts of California. Me and my friends would always adventure round and I’d always bring my camera with me, document things.

What initially drew you to using a camera?

I started taking photos in elementary school, I’d have my dad take me to the drug store to buy a disposable camera every weekend, and I’d shoot my friends. We were into BMX’ing and skating and stuff like that. Then I’d go get them developed at the drug store and put them in some funny 4×6 photo albums and cover the albums with skate stickers, so it’d look like magazine.

Do you do all your printing yourself?

These days I go to a darkroom for sure. I learnt how to in college, but it was really intense—we had to get all the colours right and it was more, like, technical. I wasn’t that into it; I was like, ‘Oh, that’s kinda just a pain in the ass, I’d never do that if I was a professional photographer.’ And then soon enough, I started putting my own twist on it; not making the colours perfect and making them a little more weird. I would try doing it in Photoshop, but it just felt cheesy to make the sky red in Photoshop, I couldn’t do that. I was like, I have to do this the analogue way.

It always looks better.

You can tell, I feel like. If you know—you know (laughs). But it’s fun, it’s definitely opened up other processes, like cyanotypes and a number of different things, just being in the darkroom and learning from different people.

I was just looking at one of your works, ‘Blue Belly’—what kind of things did you alter during the process to give it that effect?

That was part of a landscape series I was doing. I’ve always been drawn to American landscapes, because I like the idea that all roads lead home. Basically, I was driving along the highway in Joshua Tree, and I had slide film with me, wich is colour positive. Normal film is colour negative, so when you go into the darkroom it prints positive. But I only had slide film and I was like, whatever, I’ll still shoot this, this could be interesting. I discovered this mountain of graffiti while driving along the highway, and I noticed it looked like it was mostly composed by freight train drifters, like these kids that take trains across the country. It was mostly writing, just calling out America’s problems and communicating with other drifters about local information. So that was interesting for sure, and when I took that into the darkroom I noticed while printing that the colour positive result made a lizard look like a blue belly lizard, which is an actual lizard. And then, it’s a double-sided frame so on the other side is another image—I’m actually looking at it right now, it’s on my desk—so on the back-side is another shot and the same effect happened. While I was printing it, it immediately started looking like the Led Zeppelin album cover, Houses of the Holy. I don’t know, I was cracking up, me and the other person who was printing it. So, I named that one Houses of the Holy. I was like, ‘Maybe that’s how they shot that album cover?’ I have no idea, but it’s just a cool discovery.

Are there any other rules that you learnt at college that you purposely break?

After being taught my entire college career on how to make the most impeccable, colour-correct chromogenic print, now I’m doing all things not permitted in the darkroom, like cutting pin holes out of cardboard and shining a flashlight through it for a fraction of a second. I also brought found imagery from fanzines into the darkroom and had them made into cyanotypes… I tend to romanticise the handwork, labour-intensive and traditional printing of photography.

I wanted to talk to you a bit about your portraiture, because it’s such a focal point of your work. Is there a particular portrait of yours that you feel perfectly captures the personality of the subject?

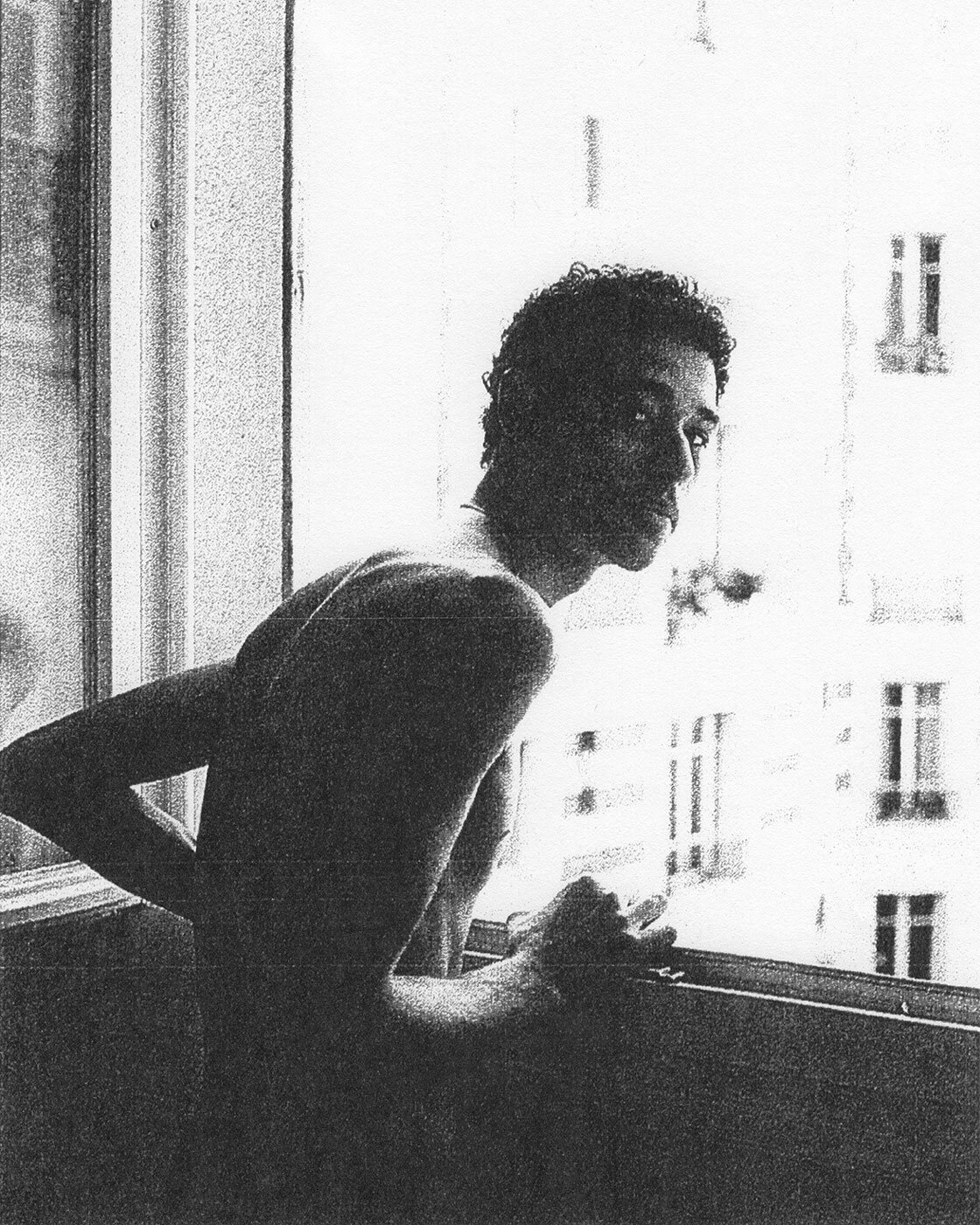

I feel like most portraits are more so a reflection of the photographer than the individual. But also, I think it really depends on the kind of photography… like, with anything that’s fashion, it’s much more aspirational and the challenge is about successfully creating this fantasy, but with photojournalism, for example; it’s more about documenting something. Back in 2018, I shot Damien Echols for New York Times, who was a part of the West Memphis Three, this group of kids who had gotten convicted in the 90’s mostly based on the fact that they were the Metallica-listening town misfits. I was excited when the Times asked me because I had just watched the HBO documentary Paradise Lost. On the day of the shoot, I arrived an hour early to do some quick location scouting and to get my bearings, and when Damien arrived, his wife pulled me aside and said, ‘We can’t shoot outside because it’s too hot out for him.’ He spent a lot of his formative years on death row, which ultimately affected the way he processes things. I ended up shooting him in a bowling alley, of all places. I found the only window in the building and had Damien sit next to it so I could get some decent light on him. The difficulty of taking his photograph I think ultimately made the portrait more interesting, because it was less editorialized.

And are there any photographers whose approach to portraiture you really admire?

Definitely. I mean, Larry Clark has had a big influence on me, and when I discovered his work beyond his most well-known work, Kids, I was obsessed. I feel like I discovered him in college, which is funny, but I spent endless hours researching his work and I admire that he had this ability to make still images look cinematic. And all throughout his book Tulsa, not a single person makes eye contact with the camera.

Really?

Yeah, so by the end of the book it feels like you just watched a movie. I just love that, I used to try and do that, like not have anyone look at me while I was trying to take photos. But that’s definitely changed, I want to take photos now where people are making eye contact.

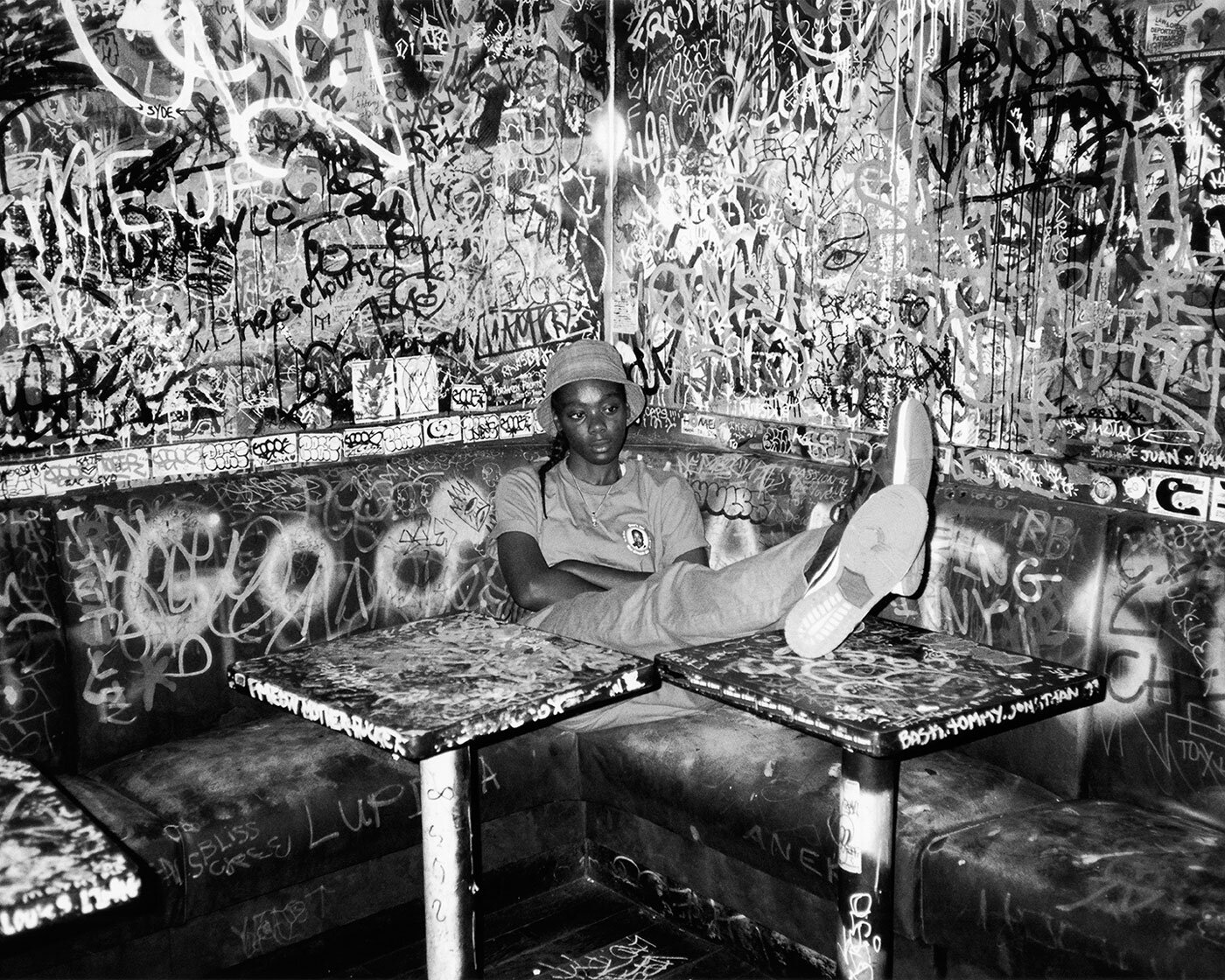

I see you’ve been shooting a bunch for Supreme too. What’s your take on skateboarding becoming so prevalent in the fashion world?

It’s so hard to answer… Skateboarding has taught me a lot about location scouting, and it’s altered how I see the physical world. I feel like I can’t even look at my surroundings the same way ever again. Especially more recently, working with Supreme and the skaters, the way that they just look at stuff, I’m always cracking up. We’ll be walking around and they’ll be like, ‘Ohhh, those stairs! That ledge!’ Just freaking out and it’s the most bizarre, weird way of seeing architecture. It’s so funny. They’re actually quite similar to architects in that way, the way they nerd out over buildings. I also feel like there’s this parallel recently I’ve noticed between filming a skate part and shooting an editorial, because there’s this same rush of emotions when you’re driving around with your crew and you’re looking for the right spot, trying to get the perfect moment and then move onto the next spot before the day is over. I’m super grateful that being a photographer can put you in a situation you normally wouldn’t find yourself in. Growing up it was my dream to be a professional skateboarder; Supreme has taken me on multiple skate trips, once to Mexico City and mostly recently to Tokyo. It’s laughable really, because I can’t skate for shit, but because of my camera I get to pretend I’m sponsored by Supreme.

Okay, I have to ask you—what was it like shooting Iggy Pop?

Oh right, I’ve got a whole story for that one. The day before the shoot, I was headed to the pool at the hotel I was staying at and I heard someone shout my name, and it was Ryan McGinley. I used to work for him. So we started catching up and he told me that he just shot Iggy Pop a few hours ago, and my immediate thought was, ‘Shit, I must have been mixed up and I didn’t get the job.’ That it was a mistake. But it turns out, he was shooting for the New Yorker and I was shooting for GQ, so I guess Iggy was just busy with photoshoots that week.

Was that in Miami?

Yes. But it was great, because then Ryan gave me some pointers on shooting with Iggy; he told me that Iggy loves listening to the blues, so if Muddy Waters was playing we should have no problem. I mean, I was a bit nervous about shooting him because he’s an icon and he’s been shot by major photographers throughout a lifetime, so it was great being able to get the low-down the day before. And then the day of the shoot, I meet Iggy on the beach and he’s just about the sweetest man on earth, which is a relief.

That’s good to hear.

Yeah, and I started to load my point and shoot and Iggy was like, ‘I really like how small your camera is, it’s less intimidating.’ And I was like, oh—when you think about it, photography is just two people looking at each other with an object in-between, so I suppose the smaller the object, the more intimacy there is between two people. It was just great being able to create a low-key atmosphere for him and subjects in the future. I do usually shoot with pretty small cameras, and most photographers lug around these giant…

Pieces of metal.

Yeah, and it’s kind of cool to have a different approach to it. Even though I’m shooting big people for big magazines.

It’s interesting to me that he even noticed that, because you would think he’d be immune to the whole process because he’s done so many shoots.

Yeah, I feel that that was definitely a cool conversation to have with Iggy Pop for sure. The bigger the icon, the smaller the camera (laughs).

I like that approach. I love the photo of him in the leopard coat standing in the palm fronds.

Oh yeah, the Celine coat, I love that one.

Did he dress himself or did you have a stylist?

[Laughs] No, if he dressed himself, he would’ve just been shirtless. That’s how he showed up.